Mountain Memories – A History of Jamestown, CO

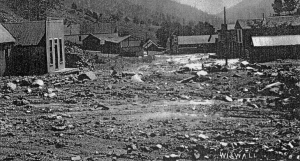

Past Jamestown Floods

There have been numerous flood events documented in Jamestown over the past century. In June 1894, flooding washed away much of the low-lying area of the Town. This flood was a result of heavy rain combined with spring runoff. In August 1913, a short cloudburst lasting approximately 30 minutes damaged bridge and culvert crossings along James Creek. Another flood occurred in 1916, destroying almost all houses along James Creek and washing away all wagon and footbridges. The Town was also flooded in 1965, and again in May of 1969, where the floodwaters left the normal channel, destroying buildings and the town water supply.

There have been numerous flood events documented in Jamestown over the past century. In June 1894, flooding washed away much of the low-lying area of the Town. This flood was a result of heavy rain combined with spring runoff. In August 1913, a short cloudburst lasting approximately 30 minutes damaged bridge and culvert crossings along James Creek. Another flood occurred in 1916, destroying almost all houses along James Creek and washing away all wagon and footbridges. The Town was also flooded in 1965, and again in May of 1969, where the floodwaters left the normal channel, destroying buildings and the town water supply.

Flood of 1969 Hit Jamestown Hard

by Silvia Pettem (originally published in the Camera 5/6/04)

During Jamestown’s flood in 1969, cars were thrown into James Creek to preserve the historic buildings. Carnegie Branch Library for Local History, Daily Camera collection.

For four straight days in early May 1969, a total of nearly seven inches of rain fell steadily in Boulder County. Nowhere was the deluge worse than in the mountain town of Jamestown, northwest of Boulder. Troubles for the residents began with rock and mud slides on the main road. Then the bridge over James Creek washed out, and flood waters began cutting away at the downtown buildings.

After a cabin fell into James Creek, residents dumped old cars into the raging waters in order to prevent the normally placid creek from completely changing course and sweeping through the center of town.

“More than the sound of huge boulders rolling down the creek, I remember the horrific sound of massive amounts of water moving, rushing down the canyon,” said Jeanney Scott Horn, a former resident of the town. Volunteer firemen ran from house to house, ordering people to get to higher ground.

By dawn, the reality of their devastation was revealed. Horn lost some personal belongings and furniture, but she had friends who lost everything. On May 6, there was no way in or out of the mountain town. The power was out, but no one could get there to repair the broken lines. Both town pump houses were washed away, water mains were either leaking or broken, and at least one outhouse was seen floating through the debris.

One man fell into the creek, suffered a serious head injury, and lost an eye. At least two women were expecting babies, and one of them was three weeks overdue.

Sheriff Marvin Nelson contacted the National Guard to try to fly in a medical helicopter, but all aircraft had been grounded because of the wet weather. As a last resort, an Army vehicle “capable of treading five feet of water” was sent in, with a doctor, from Estes Park. One of the pregnant women was evacuated over the then unimproved and “almost impassable” road up Overland Mountain.

Two additional physicians from Boulder hiked the 15 miles to the town to treat the injured man (who could not be moved) and be available to deliver the other baby.

Five days after the storm began, the sun came out. Left Hand Canyon (between Boulder and Jamestown) was still impassable, as were the roads up Four Mile and South St. Vrain canyons. The Camera called Jamestown “rain-soaked, bedraggled, and virtually cut off from the world.” Horn called it “a godforsaken mess.”

People cheered as the Public Service Company’s helicopter finally came to the town’s rescue. It brought in water pump parts to repair the communal well and 200 gunny sacks for sandbagging. Jamestown residents hastily built two emergency dikes. One protected the Jamestown Community Church and the Mercantile Building, while another kept the water from hitting 10 low-lying residences.

The airlift also brought in 48 loaves of bread, 48 quarts of milk, a case of eggs, and typhoid fever vaccine to guard against the possibility of residents drinking contaminated water.

The following day, Sheriff’s deputies managed to get another pregnant woman to Community Hospital, in Boulder, where she immediately gave birth to a healthy girl. The Camera’s final report on Jamestown stated, “The residents were digging out today, determined to build and repair and stay on their mountain.”

Helen Gilman’s Handicap a “Psychic Gift”

by Silvia Pettem (originally published in the Camera 10/18/09 and reprinted in her book “Only in Boulder: The County’s Colorful Characters”)

Daily Camera file photo.

Helen Gilman was a Boulder County native who read tea leaves and told fortunes for 75 years. Deaf from a bout with typhoid fever as a child, she was considered different from her peers. She later explained that her deafness had given her a second sight.

As an adult, she used her handicap—which she considered a “psychic gift”—to help others with their problems.

Gilman was born in 1892 as Mary Helen Sherman. She grew up in the mountain town of Jamestown where her grandparents ran the Martins Hotel and her father, Wella Sherman, worked at the Golden Age mine.

According to Gilman’s biography (“Helen: A Psychic Gift,” now out- of-print), she learned early on to follow her instincts. She claimed to have known intuitively how to escape uninjured when a circus tent in Boulder collapsed on an unsuspecting audience.

In another instance, while riding in a stagecoach from Jamestown to Boulder, Gilman slipped under the seat just before an accident killed another passenger. She learned to read tea leaves by accompanying an adult friend who performed the ritual for friends and neighbors. At age 25, she married John Gilman, a Boulder taxi driver.

Before long, the young woman was in demand at sorority and fraternity parties, where she dressed like a gypsy and amused University of Colorado students by telling their fortunes.

Gilman also opened the “Ye Old Tea Room,” located for more than six decades in her home at 624 Concord Avenue. She always began her readings with a fresh cup of loose black tea. Then she’d set the cup on a card table and instruct her clients to drink it while intonating, “The tea is bitter and so is life.”

When her clients finished drinking their tea, Gilman patted the remaining tea leaves with a spoon and placed the tea cup upside-down on a saucer. The person seeking information was asked to turn the cup three times and make a wish. Almost immediately, Gilman, adept at lip-reading, would speak rapidly in a husky voice and give personal advice on topics such as jobs and relationships.

The answers to one’s problems, Gilman told her clients, lay in pictures that she saw in the leaves that remained in the bottom of the tea cup. She admitted, however, that the tea was really just a medium to help her meet and talk with people.

Gilman was said to have radiated happiness and peace from within herself. In an interview shortly before she died, she told the authors of her biography, “I try to help people learn to listen better to their inner voice.”

Throughout the years, she increased her fee from 25 cents to five dollars, and her guest book grew to more than 80,000 signatures. Gradually, cataracts in her eyes left her nearly blind. She died of cancer in 1985, at the age of 92.

Gilman always concluded her readings the same way. “If none of this is true,” she said, “at least you’ve had a cup of tea.”

Prospector Indian Jack Died in Poverty

by Silvia Pettem (originally published in the Camera 3/14/10 and reprinted in her book “Only in Boulder: The County’s Colorful Characters”)

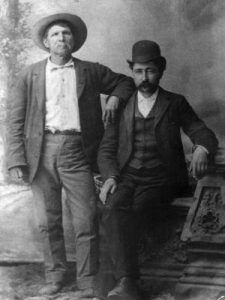

Indian Jack (left) with his partner George Bittenbender, ca 1880. Carnegie Branch Library for Local History, Boulder Historical Society collection.

Lew Wallace (“Indian Jack”) located one of Boulder County’s most prosperous gold mines. Instead of enjoying a life of leisure, his wealth slipped through his fingers, and he died a poor man.

Accounts of Indian Jack’s early life are sketchy. He was part Indian, although no one in Boulder knew much about his background. Born in New York, he was reported to have served as an Indian scout with the 14th New York Cavalry in the Civil War.

Eventually, he came to Boulder and worked odd jobs, but his claim to fame was in Jamestown, northwest of Boulder. In 1875, he prospected with partner Frank Smith. The men found valuable gold ore and staked the now- famous Golden Age Mine. Not realizing its worth, they sold out for $1,500.

The new owners deepened the shaft to 300 feet and immediately recovered a profit of $40,000. They sold the mine a couple of years later to Chicago investors for $194,000.

Indian Jack continued to prospect, but he was never as successful again. One of his partners was George Bittenbender, later ordered by the courts to the state insane asylum in Pueblo for being “crazy as a loon.”

In October, 1893, Indian Jack was struck with what the Camera called “a tedious siege” of typhoid fever. Friends took him to the county poor farm where he died at the age of 73. He was buried at public expense in a plot set aside for the indigent in Columbia Cemetery.

Four months later, the Boulder County Commissioners realized that Indian Jack was a veteran and that they had made a mistake to bury him in a pauper’s grave. Indian Jack’s body was exhumed. A reporter stated that those who doubted that “Lew” was buried in the Boulder Cemetery were “given an opportunity to see his remains.” Indian Jack was re-interred in a plot provided by the Grand Army of the Republic, an association of Union veterans.

Years later, writer Forest Crossen interviewed three men who, as children, had known Indian Jack. Roy Dunbar, one of the old-timers, said all the children liked him, even though he was “ugly enough to stop a clock.”

They recalled that when Indian Jack came out of the mountains and down to Boulder, he’d stay at the Boulder House, a hotel on the northeast corner of Pearl and 11th Streets. He cut firewood to pay for his room.

People in Boulder liked him too. According to the men who knew him, his only enemy was the whisky bottle, but he never was in any trouble.

“They had a bench over there where the Daily Camera is,” said Frank “Baldy” Sisson, another of the old-timers. “He used to get drunk and go over there and sit on that bench. Never bother nobody.”

One of his old friends said there was a marker on Indian Jack’s grave, but that has long since disappeared. No one seemed to remember much of his discovery of the Golden Age, either. The writer of his obituary called him a “drunken, harmless, good-natured fellow.”

It was the closest he got to an epitaph.

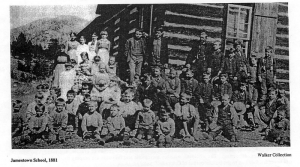

Jamestown School Has Always Been the Heart of Its Community

by Silvia Pettem (originally published in the Camera 2/20/03)

Children in Jamestown have been walking to school for 136 years. Even in the mountain town’s early years, there were enough children to bring about the formation of School District Number 11, the oldest mountain school district in Boulder County.

Children in Jamestown have been walking to school for 136 years. Even in the mountain town’s early years, there were enough children to bring about the formation of School District Number 11, the oldest mountain school district in Boulder County.

Today, the elementary school of 18 students is threatened with consolidation. When the school has a play or fundraiser, however, the whole town turns out to support it. The Jamestown School has always been the heart of its community, and the locals don’t want it to close.

Current resident David Mans attended the Jamestown Elementary School in the 1970s. He moved away for several years, but he returned to the town eighteen months ago with his wife and two sons. The school had a lot to do with his decision to move back and, like other parents, he values the small-town-family-oriented atmosphere.

Jamestown had its beginnings in the early 1860s, when a group of prospectors, including a man named James Smith, found rich deposits of galena, lead, and silver in a mountain valley west of Boulder. The resulting mining boom brought in hundreds of miners, plus a few families.

In 1866, when residents applied for a post office, they asked to be called Camp Jimtown. However, the U.S. government, exercising their own prerogative, granted them the name of Jamestown. Today the community goes by either name although, to the old-timers, it will always be Jimtown. Classes were held in private homes beginning with the formation of the school district in 1867.

Gold discoveries in the 1870s caused the town to boom again, and, by the early 1880s, residents constructed their first school building. The one- room log structure is still standing and is the rear portion of the house at 3400 Overland Road, the third residence west of town. Some classes were held in the evenings, since many of the older boys also worked in the mines.

More mining activity in the early 1880s brought additional families with more children. School terms lasted six months, with 50 or 60 students under one teacher. One student was Douglas Fairbanks, who grew up to be the well-known actor of the silent screen.

By the 1890s, children in outlying mountain ranches attended the Stony Lake School (east of Rock Lake in today’s Bar-K Subdivision). But their classes only were held in the summer, so several of the area’s students boarded with families in Jamestown and went to school there, as well.

With a continually swelling enrollment, a second Jamestown School was built in 1897, up on the hill south of James Creek. One room held grades one through four, and another room was for grades five through eight.

That frame building was razed to make room for the current (third) elementary school building, which dates from 1953. (The Stony Lake School was consolidated with the Ward School in 1928.)

Five of the children come from the Bar-K neighborhood, just as their predecessors did in the days of the Stony Lake School. The others live in Jamestown. Mans, one of those Jamestown parents says, “I still choke up thinking of the first couple walks up the hill to the school with my son, in the same footsteps I walked 30 years ago.”

Back to Top

Journal of Mamie Murphy Lang

The Man Behind Andersen Hill

By Barbara Byrnes-Lenarcic

Jamestown’s gray and grainy landscape is a path into the past. Street names once uttered without a thought now have a persona. Take Andersen Hill. The road may be washed away, but the spirit of Edward K. Andersen, the Hill’s namesake, is embedded in the dirt cheering us on.

Andersen was born in Cripple Creek, Colo. on Oct. 26, 1902. Ed’s father, a miner, was always looking for a new vein. That quest brought the elder Andersen to Jimtown around 1910. Young Ed had no interest in mining. In 1916, he was busy graduating from Adams City High School and running a creamery on Alameda in Denver. Then, the Depression hit. The dairy went sour. Ed needed work. His father talked up Jamestown, so Ed decided to give mining two weeks. That whim turned into a 27-year gig at the Wano Mine, located west of Ward St.

Ed joined the Jimtown community. He first lived at 134 Andersen Hill with his mother. That house, later owned by Daniel and Kelly Kennelly, was destroyed during the September 2013 event. The foundation can be seen across from the Andersen Hill footbridge built by the Baptists.

Andersen then moved to 81 Main St., the site where Val and Quinter Fike built their current home. Wanting a vegetable garden, Ed added rich black soil to the land. He sold his produce to Ideal Market on north Broadway in Boulder. Anderson also raised chickens. Neighbors stopped by Ed’s place to buy chickens and eggs.

Ed’s community service ran the gamut. According to a Jan. 17, 1979 article in the Sunday Daily Camera published on his first and only wedding day – Ed was 76, his bride was 62 – Ed was the Town Marshal in 1938, Water Commissioner in the 1940s and on the Town Board several times. He also ran the pool hall across from the Mercantile. At midnight, after the Saturday night dances in the Town Hall, Ed served sandwiches so folks would sober up before driving down James Canyon.

Andersen died on Sept. 30, 1984 at the age of 81. He is buried in the Jamestown Cemetery. Ed’s headstone is the last one up the hill from the Sapp Family plot. Andersen rests in a peaceful place surrounded by wild purple/white irises. Ironically, this man, who was so proud of his Danish heritage, lies beneath a stone engraved with Anderson, the Swedish version of his name.

Why and when Andersen Hill was named after Ed is a mystery. Still, the explanation may be quite simple – Andersen was a character living at the bottom of a hill that needed a name for a street sign.

Ed Andersen is buried in Jamestown. Sadly, his name is misspelled on his headstone.

Springdale Was a Celebrated Spa

by Silvia Pettem (originally published in the Camera on 9/11/03)

It’s always fun to find something left of a ghost town or long- forgotten community. Springdale, two miles east of the mountain town of Jamestown, is a perfect example. Few of the casual tourists or busy commuters who drive James Canyon today even know that Springdale existed, although it once was a lively resort and spa, then resurrected years later for its “healing” mineral waters.

The Boulder County News of June 30, 1876, announced that a 14- room hotel, called the Seltzer House, was under construction at the “famous mineral springs” at Springdale. The writer stated, “When ready for guests, it will be the neatest and coziest place to spend the summer months in the whole mountain region.”

The springs were regarded as a “fountain of youth” and were said to have contained “all the medicinal properties of the most famous springs of Germany.” The locals called the naturally carbonated waters “lemonade springs.” The area was dotted with gold mines, and promotional literature raved about the “romantic scenery of the most remarkable character.”

Within a few years, the resort included a bath house, riding stable, bowling alley, drinking fountain room, bottling plant, and saloon. The population of 300 established a post office and even had enough children for the community to build its own one-room frame school.

Several of the original buildings were washed away during the flood of 1894. Many of the rest were destroyed in 1903 when an overturned oil lamp in the hotel started a fire. However, a few residents stayed, served by the Springdale post office which remained open until 1911.

In 1916, the town-site was purchased by Dr. William Harlow, dean of the University of Colorado Medical School. By 1920, authors of a Colorado Geological Survey Bulletin determined that the springs had the highest radioactivity of any mineral waters in the state. In the mid-1930s, rerouting of the James Creek road covered three of the four springs.

The property was purchased again, in 1946, by Al Freel whose wife believed that the water had cured her of numerous ailments. The couple renamed the area Curie Springs after Marie Curie, the discoverer of radium.

Freel, who was educated as a petroleum exploration engineer, urged visitors “to drink the cool, effervescent and agreeable water, and hear the released energy vibrations of health in energy waves.” He called the glowing light flashes of electrically charged particles in the water “plasmatron.”

In 1949, Freel built a small still-standing stone building which he called the “Curie Inhaling Room.” There, Freel charged people two dollars per visit to “breathe the gases that flow with the water.” Freel claimed that his treatments would cure everything from arthritis to indigestion. Through the mid-1960s, he also bottled the water and shipped it all over the country.

By then, Boulder County Public Health officials began to question the radon levels at Curie Springs, and Freel’s operation was discontinued. According to Mark Williams, currently with the health department, it was in the 1960s that public health officials started to realize that the water wasn’t necessarily therapeutic. “However, some people still believe that radon caves are therapeutic,” he said. “Public health officials don’t always reflect the public consensus.”

The tiny inhaling-room building is recognizable today by its corrugated metal roof, on the creek side of the James Creek road. Just down the road on the uphill side is a log house which is said to date from the original Springdale community.

To reach the site from Boulder, go north on the Foothills Highway (U.S. 36), turn west onto Lefthand Canyon Drive (Boulder County 94), and stay on 94 toward Jamestown. The Springdale/Curie Springs site is one mile west of the Ward turn-off.

History Repeated in Rehabilitation of the Jamestown Town Hall

by Silvia Pettem (originally published in the Camera, 10/25/09)

In the mid-1930s, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt created a federal work relief program for the unemployed. Called the Works Progress Administration, it resulted in the construction of public works projects all over the country, including several in Boulder County. Jamestown’s Town Hall—built in 1935 with local materials and labor—was one of the first.

Seven decades later, the rustic stone building is receiving much- needed major structural repairs. ―History is being repeated as government grants and local materials and labor, again, are getting the job done,‖ said Kathryn Barth, the project’s architect.

The western Boulder County mountain town of Jamestown was settled in the 1860s as a gold mining camp. During the Great Depression— when the town hall was built—the government-set price of gold had been raised enough to revive the mining industry, but many men still were out of work.

With the WPA program in place, the town squeezed its new public building between the community’s only church and the Jamestown Mercantile which, at the time, served as a post office and gas station. Once completed, the town hall also hosted community events—from pancake breakfasts to a polling place. Most recently, the building has been used as a theater for the Jamestown Area Artists and Musicians, known as JAM.

Meanwhile, the roof had begun to sag, prompting the construction and repairs being done today. Barth defines this current work as rehabilitation, with elements of restoration.

In recent weeks, today’s construction crew added new rafters to the old, and soon will stabilize the building with steel cables. Rob Koehler, a local stone mason, also re-pointed much of the original mortar in the building’s 12-inch thick stone walls. Inside, the building’s stone fireplace is being cleaned up, and the original wood floors will be refinished.

The crew are also building a 16-by-38-foot stone-faced addition on the east side of the historic structure that will house the town clerk’s new office – paid for with a grant from the Department of Local Affairs, a state agency.

In 2003, the original town hall was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The prestigious designation states that the building is worthy of preservation, but it doesn’t provide protection from demolition. That was ensured in 2007, when the Boulder County Commissioners granted the building county landmark status for its association with the development of

the Jamestown community and its significance as an example of a ―New Deal Era vernacular stone structure.‖

Local land-marking also made the building eligible for preservation grants, including Colorado state funds for the roof and stone repairs, and a Boulder County grant for the restoration of the building’s original windows.

“The town hall’s been used for 74 years, and I hope it will be enjoyed for at least 74 more,” said Barth. It’s been a very satisfying project— updating the old for use in the future and involving the local community, as well.